In praise of the Local Property Tax

We should be raising far more from the Local Property Tax than we do. Instead, successive governments have eroded and degraded it.

The Local Property Tax (LPT) has been in the news following Dublin City Council’s recent decision to end a 15% rebate which it has applied since the tax was introduced in 2013. This has generated some criticism, including from Cllr. Daithí Doolan of Sinn Féin who was quoted as saying the tax is unfair because the “prince pays the same as the pauper” and Cllr. Pat Dunne of Independents4Change who decried the changes on the grounds that the LPT “doesn’t take into account ability to pay”.

This is just wrong. It is clear that the LPT raises much more from better-off areas and households, even before one gets into the various provisions that allow for the tax to be deferred by those on low-incomes or on grounds of hardship.

The LPT is one of the least bad taxes around, with smaller economic costs than income tax, PRSI or VAT. As a result, there is a strong argument that we should be raising more from it and less - or relatively less - from other taxes. Unfortunately, successive Governments have taken the opposite approach, making changes that have eroded and degraded the LPT over time.

Increasing the LPT raises more from better-off areas and households

The LPT is paid by owners of residential property in Ireland each year by self-assessment. The amount of LPT paid is based on the estimated valuation of the property, with those valued at less than €1.75 million paying an amount that is determined by which of 19 valuation bands it falls into.1

Properties falling into a higher band are subject to more LPT with, for example, properties valued at less than €200,000 (the lowest band) paying €90 per year; properties valued at €437,501 – €525,000 paying €495 per year; and properties valued at €1,662,501 – €1,750,000 (the highest band) paying €2,721 per year. The rebate of 15% applied by Dublin City Council is then applied, reducing the LPT by €13.50 for properties in the lowest band and €408.15 for properties in the highest band.

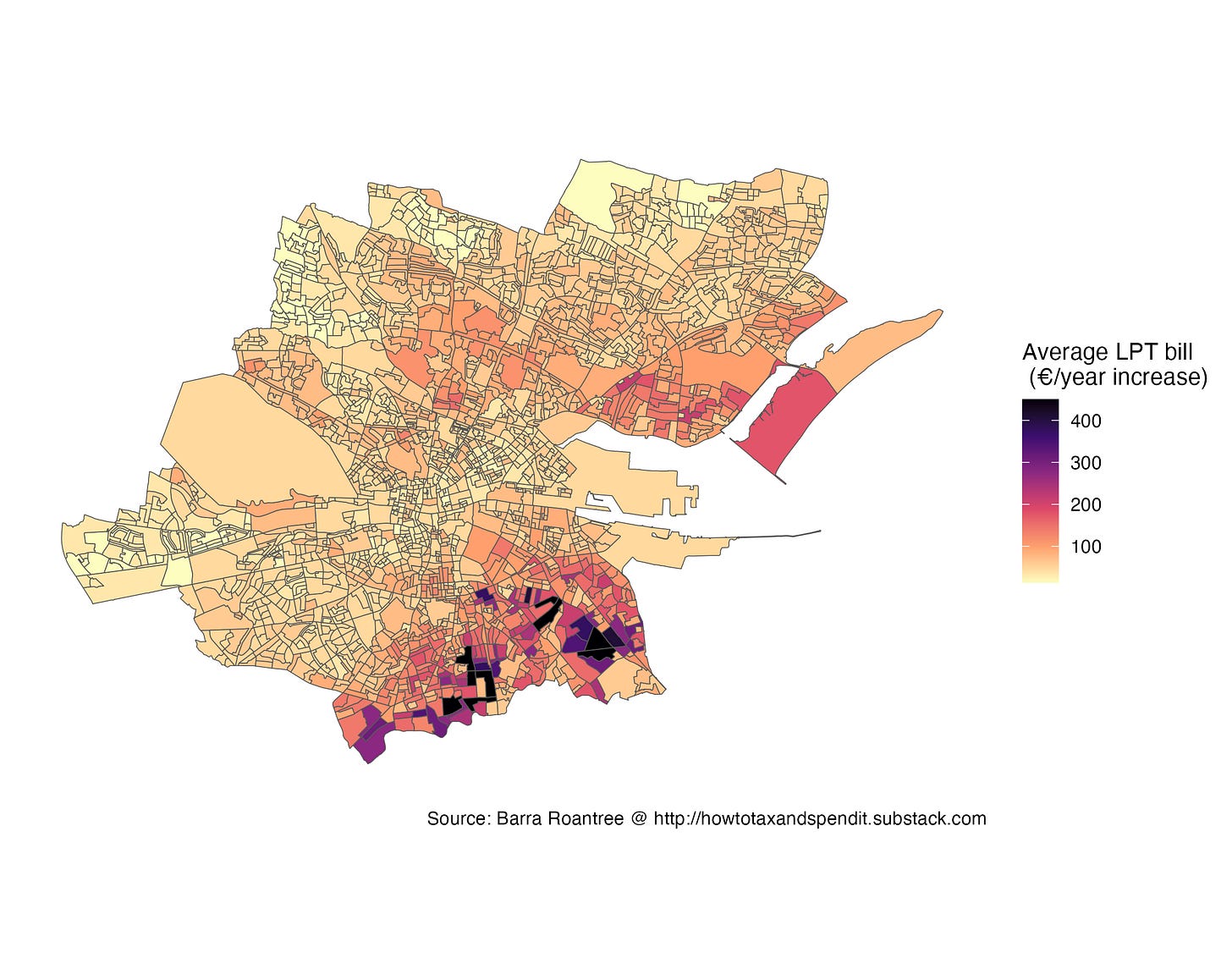

As a result, ending the 15% rebate raises more in areas with higher property prices. This is shown in the map below, which uses data published by Revenue on the average LPT band by CSO Small Area level to estimate the average change in LPT bills across Dublin City from ending the 15% rebate. Darker colours on the map mean a larger increase in the average LPT bill, and lighter colours a smaller increase.

The average increase varies from €13.50 per year in areas like Ballymun, Ballyfermot and Finglas (where the average property is in the lowest valuation band) to more than €408.15 per year in parts of Rathmines, Rathgar and Dublin 4 (where the average property is valued at over €1.75 million). For almost 90% of Small Areas, the average increase in LPT is less than €100 per year (and so shaded in yellow or orange above).

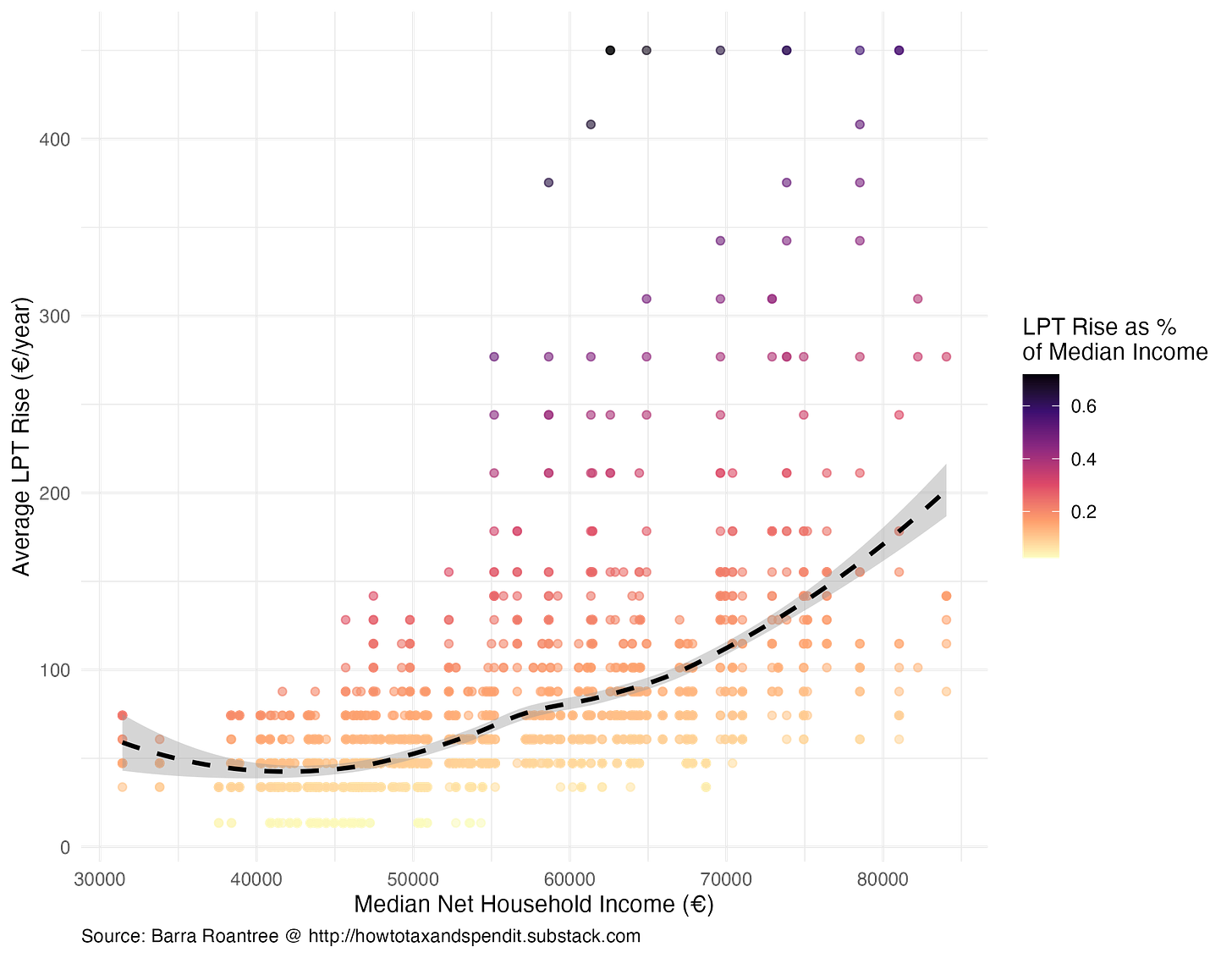

The next figure plots the average LPT increase against average income. This uses data on median net household incomes published by the CSO at Electoral District level and shows that the average rise in the LPT is much larger for higher income parts of Dublin City, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of median incomes.

In areas that have below the Dublin City median income (<€53,476), the average LPT increase will be €48.60 euro per year or 0.105 per cent of median net household income. In areas that have above Dublin City median incomes, the average LPT increase will be €91.20 euro per year or 0.142 per cent of median net household income.

All this shows that it simply isn’t true that the “prince pays the same as the pauper”. People with high incomes tend to live in larger houses in more expensive areas. As a result, they pay far more in LPT and of any LPT increase, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of their income.

While there will of course be cases where someone with low income owns and lives in an expensive house, this is far less common than sometimes suggested. It is also precisely the reason for various provisions to allow for the payment of LPT to be deferred. For example, in addition to personal insolvency and quite general hardship grounds, a full deferral can be availed of by a couple who own their home outright with gross incomes of under €30,000 per year: more if they have a mortgage on the property.

The LPT is one of the least-bad taxes around and should be increased substantially

The above shows that despite what is sometimes claimed, the LPT is a progressive tax in that it raises more from better-off areas and households.

The LPT is also among the least economically damaging type of tax. This is because the supply of residential property is relatively fixed, with limited options available to property owners to respond to the tax. Unlike, for example, with income tax or PRSI, someone cannot lower their tax liability by reducing the number of hours they work or the effort they put into trying to get a promotion.2

This reduces what economists call the deadweight loss from taxation and is one of the reasons why the report of the last Government’s Commission on Taxation and Welfare (which I was part of) recommended “that revenues derived from LPT should increase substantially over time”. The Commission recommended this as part of moves to increase the overall level of revenues raised from taxes as a share of national income, aimed at addressing challenges of fiscal sustainability in the medium-to-long-run brought about by factors including an ageing population, climate change and an over-reliance on transitory corporation tax receipts.

However, even if you disagree with the idea of raising taxes as a share of national income, there is still a strong argument to support increasing the LPT to replace other sources of revenue from more economically damaging taxes. For example, one could use revenues from a higher LPT to cut income tax rates which deter people from working additional hours, or to reduce development levies on new build housing to boost badly needed supply of new housing (something I think there is a good case for and I’ll try write about soon).

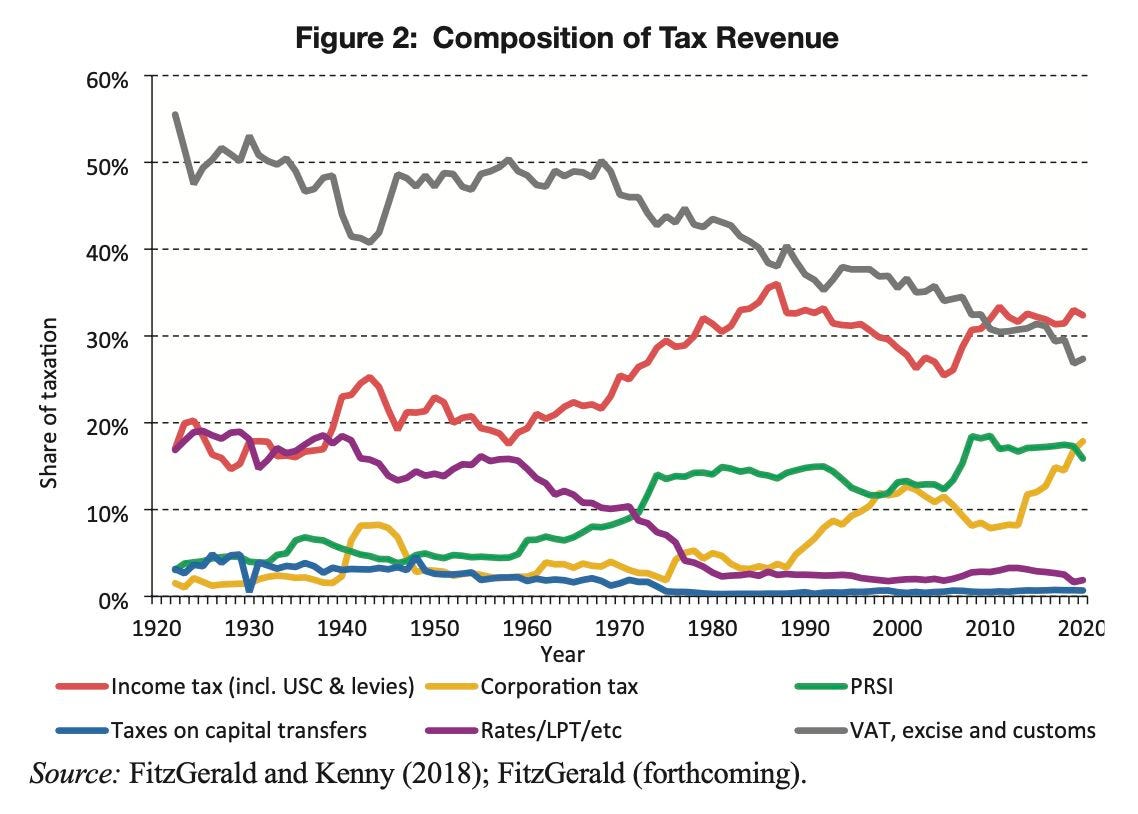

Raising LPT could also help reduce the narrowness of our tax base (with its worrying reliance on highly concentrated corporation tax revenues that are extremely sensitive to the activities of largely US multinationals) and help reverse what I think is an under discussed long-term trend in Irish taxation: the shift towards taxes on personal and corporate income, and away from property and consumption.

This is shown in the Figure below, taken from a recent paper of mine in the Economic and Social Review. It shows that while receipts from property taxes used to make up a fifth or so of Irish tax revenues in the first decades of the state, this declined sharply over the 1960s and 70s alongside those from taxes on consumption. The shift away from these taxes went hand-in-hand with a shift towards taxes on income: first, on personal income (including PRSI) and then - from about 1990 - on corporate income. Reversing this trend has a lot to recommend it given the smaller economic costs that arise from taxing property versus income.

Instead, successive Governments have acted to erode and degrade the LPT

Unfortunately, successive Governments have taken the opposite approach, making changes that have eroded and degraded the LPT over time.

Consider that the LPT raised just shy of €500 million per year in the years after it was first introduced in 2013. Despite house prices having more than doubled and the housing stock having increased by more than 100,000, the latest figures from Revenue show that the tax is expected to raise only €543 million in 2024. This means that receipts from the LPT have almost halved from 0.33 per cent to 0.17 per cent of (modified) national income between 2014 and 2024, and from 0.85 per cent to 0.43 per cent of total tax revenues.

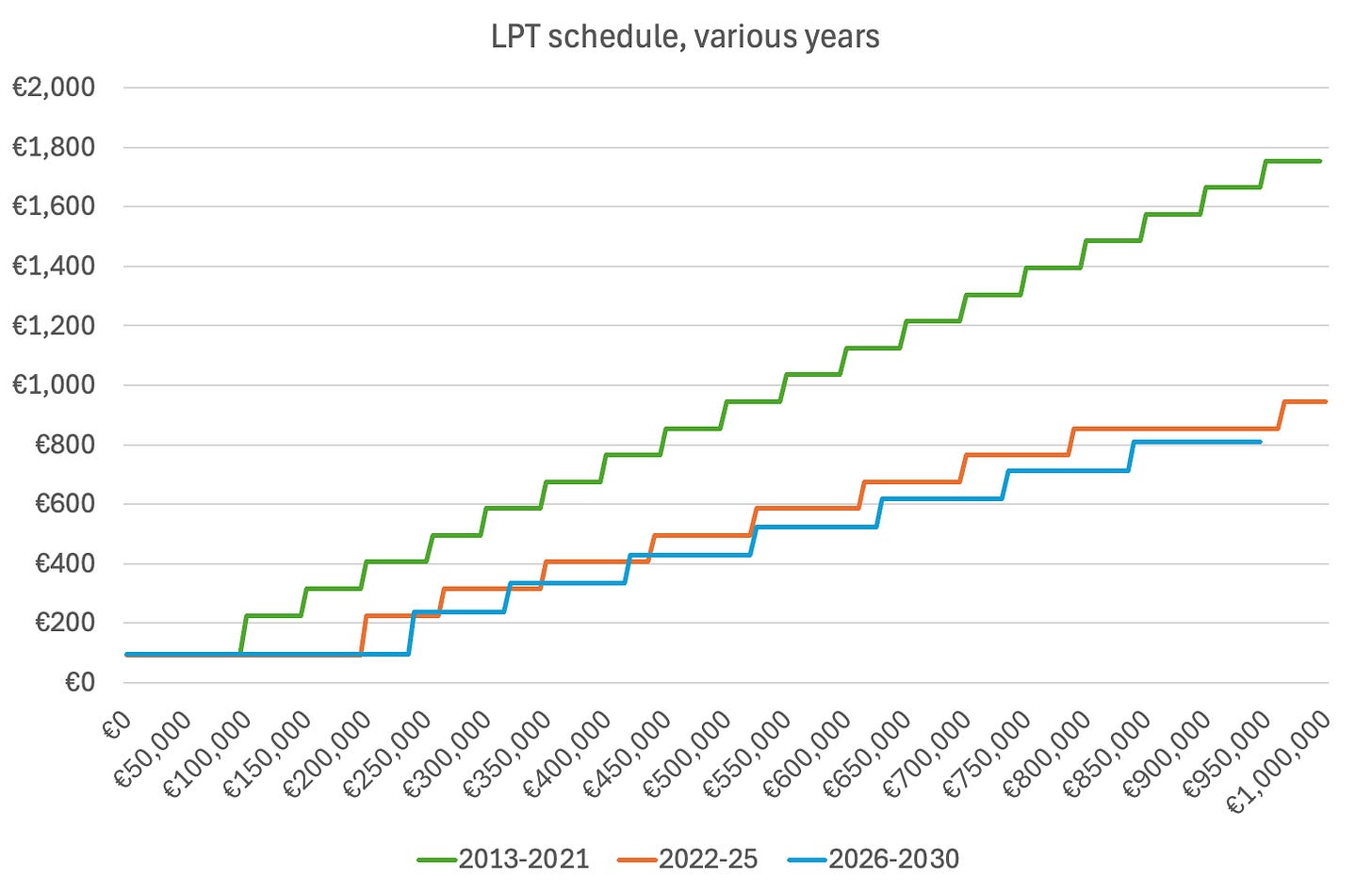

The weapon of choice for successive governments to achieve this has been a widening of the valuation bands alongside a reduction in the effective rate at which the LPT is applied. This means that the LPT now raises far less from a property of a given value than it did in when the tax was originally introduced.

The Figure below plots the LPT schedule that applied from 2013-2021 and 2022-2025 along with that which the Government have announced will apply from 2026-2030. This shows that while a property valued at €350,000-€400,000, for example, was subject to an LPT of €675 per year between 2013 and 2021, the owner of such a property currently pays €405 per year and will from 2026 pay just €333. This amounts to a halving of the average effective rate charged on properties valued at between €100,000 and €1,000,000, from 0.18 per cent to 0.09 per cent.

The rationale given for these changes was to “prevent a significant increase in liabilities” arising from property price growth, with the Minister of Finance quoted in the Department press release announcing the changes stating that without reform “approximately 70 per cent of households would go up at least one valuation band”. As the Minister presumably knows, that’s usually how taxes work. For a given tax rate, an increase in the tax base (here, house prices) will increase tax liabilities.3

No one would be taken seriously if they suggested that we should cut rates of VAT in half because expenditure has increased substantially. Nor if they suggested we should cut rates of income tax to ensure that someone who paid, say, €2,500 in income tax when they earned €25,000 pays the same after their earnings increase to €50,000. Yet this is precisely the spurious argument that has been made by successive governments, with little challenge from the opposition.

It can only be hoped that our exceptional reliance on corporation tax receipts from US multinationals doesn’t come to an abrupt end, with serious consequences for the health of the public finances. But if it does, politicians who have held the role of Minister for Finance should be judged harshly for the way they have eroded and degraded the LPT.

LPT is charged on properties valued at more than €1.75 million at a progressive rate based on its valuation: 0.1029% of the first €1.05 million; plus 0.25% of the portion of the declared market value between €1.05 million and €1.75 million; plus 0.3% of the portion of the declared market value above €1.75 million. A property valued at €2 million in 2024 would therefore have a LPT liability of €1,080.45 + €1,750 + €750 = €3,580.45.

Individuals could reduce their LPT liability by making their property less valuable, for example, by avoiding making improvements or an extension that they would have in the absence of the LPT. In this way, an LPT is more economically damaging than, say, a pure Land Value Tax which is levied on the unimproved value of all land. However, there are a number of reasons for why one might also want to tax the value of improvements for residential property: see the excellent discussion in Chapter 16 of Tax by Design: the Mirrlees Review of Taxation (available free online here).

There is a distinction here with the issue of ‘fiscal drag’ that often arises in the presence of a progressive tax schedule. This refers to the situation whereby a failure to adjust the threshold above which a higher marginal rate applies results in the effective (average) rate of that tax increasing when the tax base rises. Given the effective rate of LPT is the same across bands for properties valued at less then €1 million, this argument does not apply (or rather, applies only to the upper limit of the highest valuation band).

Great piece Barra. Part of the political problem is that we seem to dislike with even more intensity taxes where we have to make a payment (LPT, CAT) rather than suffer a deduction or include in a price (IT, VAT). Comparing average LPT with average IT or VAT demonstrates how daft this is for both princes and paupers.

Excellent piece, Barra