The parties spending plans

Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin all have serious questions to answer on their spending plans

After what feels like an eternity, the 2024 General Election campaign is nearing its conclusion with the three largest parties – Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin – having all published their manifestos. These outline a dizzying array of promises (the specifics of which I’m not going to get into in this post) alongside – buried deep in the appendices of each manifesto – what the parties are planning to spend over the coming years.

You might have heard or read some coverage of these plans in the media, but you would be none the wiser for what the parties are actually planning to do over the next 5 years if you did. Reports repeated claims of an “extra €52bn spending proposed” by Fine Gael, and a “€56bn spending plan” from Sinn Féin: all completely meaningless figures. €52bn per what? Per year? Over the next Government’s term? And in total, or in addition to existing plans?

To be fair to the folk covering these manifesto launches, the parties haven’t made it easy to work out what they are promising and how this differs to what is currently planned. Rather, they have bundled together some annual and some cumulative figures to give a nice, big – but not too big – figure which will attract attention, but with enough jargon and bluster they can deflect questions if necessary.

Here I set out what each of the three largest parties are planning in terms of government spending over the coming years, analysis which is based on a spreadsheet that I’ve assembled from the various manifestos and published online here.

The key message to take away is that all of the parties are promising huge amounts of extra spending, but have serious questions to answer including:

“how are you going to fund your spending plans and what will you prioritise if the glut of corporation tax revenues stall?”, and

“how you are going to deliver the extra investment you’re promising without (further) pushing up prices in the construction sector?”

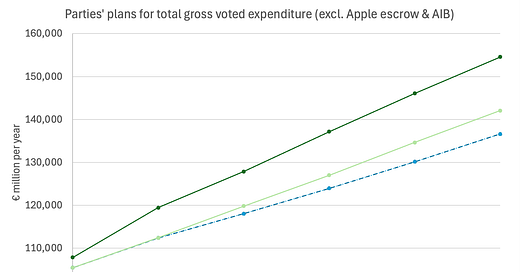

Figure 1 below shows how much each party says they will spend per year over the next 5 years, and how this compares to what the outgoing coalition government budgetary documents say was planned over the same period just a month ago. This is for a measure of government spending called “gross voted expenditure” which is comprised of the - largely - central government department spending approved by a vote of the Dáil each year (hence the name). It is not comprehensive, excluding much social welfare expenditure, EU budget contributions and the (“own-resource”) expenditure of government bodies including local authorities. But gross voted expenditure is the only aggregate measure of spending each of the three largest parties have provided information on (a big problem in itself which we’ll return to below).

The dotted black line shows the outgoing government planned for spending on this measure to rise from €105.4 billion per year in 2025 to €136.6 billion per year in 2030: an increase of 29.6%, or €31.2 billion. This amounts to voted expenditure rising by just over 5% per year on average, roughly in line with the outgoing government’s stated (though never obeyed) fiscal rule.

While Fine Gael say they will stick to these plans, both Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin say they will increase gross voted expenditure faster than this. Fianna Fáil now say voted expenditure will rise to over €142 billion per year in 2030: an increase of 25.1% or €37 billion per year, almost €6 billion per year more than set out in last month’s budgetary documentation. Sinn Féin have promised to increase gross voted expenditure even further, to €154.5 billion per year in 2030: an increase of €49.1 billion per year or 45.5% by 2030.

Despite the large differences in overall voted expenditure plans, Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin say they will spend similar amounts on current (day-to-day) voted expenditure: €122-€125 billion per year by 2030, an increase of between €31 billion (Fianna Fáil) and €34 billion (Sinn Féin) per year from its forecast 2025 level. Fine Gael say they will spend substantially less on current voted expenditure at €117 billion per year by 2030.

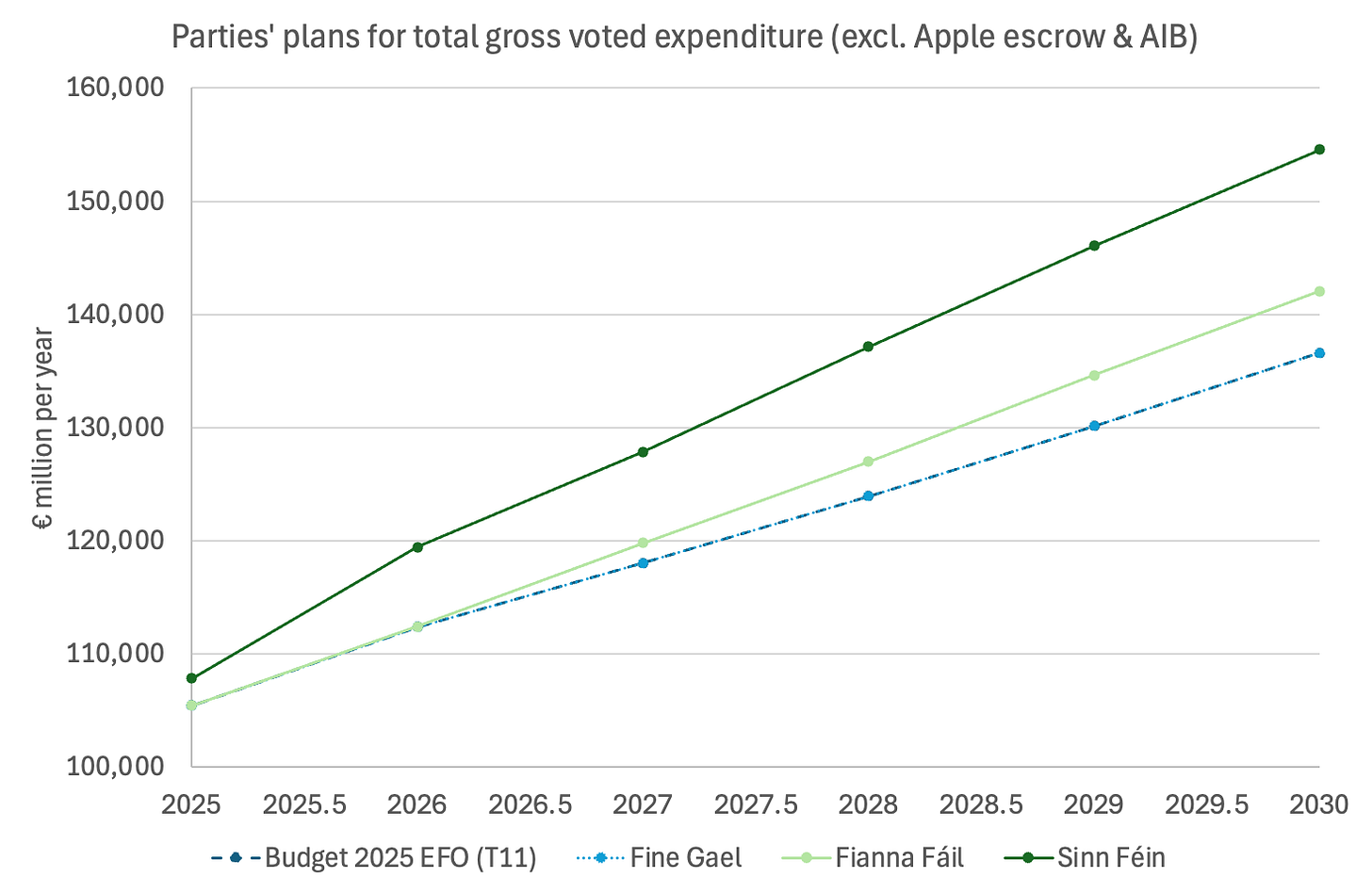

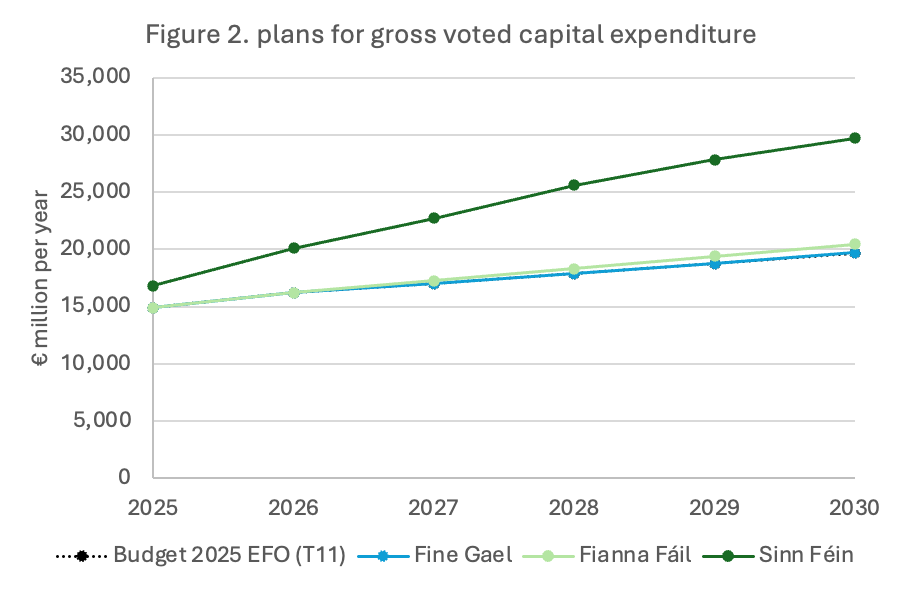

The biggest difference between the parties, however, lies in their plans for voted capital expenditure, that is spending on roads, infrastructure, housing etc. Figure 2 shows this for the three parties, with both Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael largely sticking to the plan outlined in last months’ budget for voted capital spending to rise to about €20 billion per year by 2030. By contrast, Sinn Féin are proposing much larger and faster increases in capital spending, with their plan to increase this to almost €30 billion per year by 2030!

But that’s not all. Each of the three parties are committing to spending the (~€14 billion of) funds arising from the Apple judgement of the Court of Justice of the European Union on capital expenditure over the next 5 years, with Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin also planning on spending the (~€3 billion) proceeds of AIB share sales. On top of this, Sinn Féin are planning on increasing non-voted capital expenditure – in particular, capital spending on housing by Approved Housing Bodies etc – by €9 billion a year.

The best way to compare the parties capital expenditure plans is therefore to consider what each party are saying they’ll spend over the period 2025-2030, as in Figure 3 below. This shows that while Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are planning to spend around €120 billion over the period (€15-20 billion more than the plans published a month ago), Sinn Féin are pledging to spend €170 billion: an enormous difference!

Given the economy is operating at (if not well above) capacity, this raises obvious questions about the ability of the next government to actually additional deliver additional infrastructure for all this extra spending. For example, there are already regular stories about shortages of construction and craft workers, with warnings this is already hampering efforts to increase the number of homes we are building.

Where are the extra workers going to come from to facilitate the huge increases in capital spending each party - but particularly Sinn Fein - are proposing? Migration? Banning/taxing commercial office or other unfavoured kinds of investment? How to manage this “conflict between the need for public investment and the constraints on investment” was the subject of an ESRI report earlier this year, and is something whatever parties are in government next will need to think very carefully about. Sadly, it isn’t evident that any have yet.

A caveat to this comparison of capital spending is that it doesn’t include non-voted capital expenditure commitments by Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael (although they are unlikely to change the qualitative pattern). Nevertheless, that omission points to a wider problem with the parties spending plans, namely that they are all silent about a large chunk of government spending: non-voted current expenditure.

As noted above, voted spending excludes much social welfare expenditure, EU budget contributions and the (“own-resource”) expenditure of government bodies including local authorities. In 2025, “total general government expenditure” – which includes these and some other components of spending – came to €131.3 billion, almost €26 billion (or 25%) more than the total voted government expenditure measure the three parties focus exclusively on. Ignoring such a large share of government expenditure suggests a lack of seriousness by all three parties in their approach to the public finances.

This lack of seriousness is also displayed in the cavalier way each party proposes to finance increased public expenditure: to bank on the glut of corporation tax receipts from a handful of US multinationals continuing indefinitely.

Economists have cautioned about the risks from this overreliance for many years, warnings that while acknowledged by (some) government Ministers have prompted only limited actions in response. For example, the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council recently estimated that the government is “only saving half of the €11.5 billion of corporation tax windfalls it is collecting”, without which “Ireland would be in a large and growing deficit”.

The recent (re)election of Donald Trump as President of the United States may well represent the crystallization of these risks, particularly with his expected nomination of Howard Lutnick and/or Robert Lighthizer to key economic positions in his administration. Both regard the fact that Ireland (or indeed any country) exports more goods to the United States than it imports as something to be remedied, with tariffs the instrument of choice.

While founded in a reductionist mercantilist logic, the antagonism of both to the activities of US multinationals in Ireland is in other ways very understandable. Much of the activity of these firms in the pharmaceutical and technology sectors amounts to shifting profits to Ireland to avoid paying taxes in the United States (largely the result of US laws rather than Irish laws imo, but that’s beside the point).

We should not therefore be surprised if an “America First” administration takes action to cajole or coerce US multinationals to relocate production (and/or profits) back to the US. This could quite easily adversely affect the flows of foreign direct investment that have done so much to improve economic prospects in this country, not to mention the corporation tax receipts that underpin the parties spending plans.

Not that you would know this from the promises the three largest (and some smaller) parties are making. Indeed, rather than putting forward ways we can broaden the tax base to mitigate the risks our over reliance on corporation tax revenues brings (as recommended by the Commission on Taxation and Welfare), all three are proposing non-trivial packages of tax cuts totalling between €3 billion (SF/FF) and €7 billion (FG) per year by 2030. This includes the effective gutting - in slightly different ways - of the Universal Social Charge, one of the few measures brought in over recent decades to broaden the tax base.

As Cliff Taylor wrote in the Irish Times this week, a “real issue for the parties is how they would deal with this [loss of corporation tax revenues] and what parts of their programme would be lost if the resources available were less than expected. None have been clear on this.”

Judging from the tenor of the campaign to date, there is no reason to expect this to change by polling day next week.

Note: this post was amended at 3.51pm Sunday 24th November to update the current voted expenditure figures following a clarification from the Fine Gael press office that their total voted expenditure figure included the money to be spent from the ECJ Apple judgement. You can read how these revised numbers raises issues about the credibility of all three major parties’ spending plans here.